Oxygen Journalism: Why 'Both Sides' Is Killing the News

Corporate media keeps mistaking “debate” for journalism—and the loudest liars keep winning just by getting a seat at the table.

Kristoffer Ealy is a political scientist, political analyst, and professor in Southern California. He teaches American Government and political behavior, with a focus on political psychology, voting behavior, and political socialization. Subscribe to his Substack, The Thinking Class with Professor Ealy.

A common term I use in my writing—especially when the subject is CNN or Piers Morgan’s YouTube show—is oxygen journalism. Most of the time, I try to give enough context clues around the phrase that people can piece together what I mean without me stopping the whole article to define it like we’re in the middle of a vocab quiz. But a few readers have asked me about the term, and honestly, that’s fair. So I figured now is as good a time as any to explain what I mean when I say it.

But first, a little backstory.

Back when I was younger and filled with more angst than I carry now, one of the recurring themes of my adolescent and young adult life was wasting time with people whose lease in my headspace should’ve expired a long time ago. I remember after a particularly bad breakup with a former girlfriend, I spent months being angry and bitter. My mother finally caught me on a particularly rough day and said, “Kristoffer … you’ve been done with this girl for months. Why are you still giving her oxygen?” What she meant was simple: I was giving that situation room to keep suffocating me. I was feeding it. I was keeping it alive in my head long after it deserved to be dead and buried.

Then fast forward to right after I completed my undergraduate degree. I was applying to jobs nonstop, and there was one job I really wanted at a television station I interned at. I truly thought I’d get it. I didn’t. And I complained about it to everyone who would listen. I vented to a few mentors, too. One of them at PCC, Mrs. Samuels, was sensitive to how disappointed I was, but she still hit me with the same concept: “You do not need to give that station any oxygen. You’ll find somewhere else to work.” Again—stop feeding it. Stop keeping it alive. Stop letting it take up space it no longer deserves.

So after hearing “oxygen” used that way enough times, it became part of my own vocabulary—something I’d throw out to friends, siblings, and whoever else I thought was giving life to a situation that didn’t deserve it. And we all know what oxygen is and why we need it. That part isn’t complicated. The part that gets complicated is what happens when oxygen becomes a metaphor for attention—especially in media—because attention isn’t neutral. Attention sustains. Attention keeps things alive. Attention can make something small feel big, something unserious feel legitimate, and something evil feel like just another topic that deserves a calm, balanced, respectable debate.

That’s oxygen journalism.

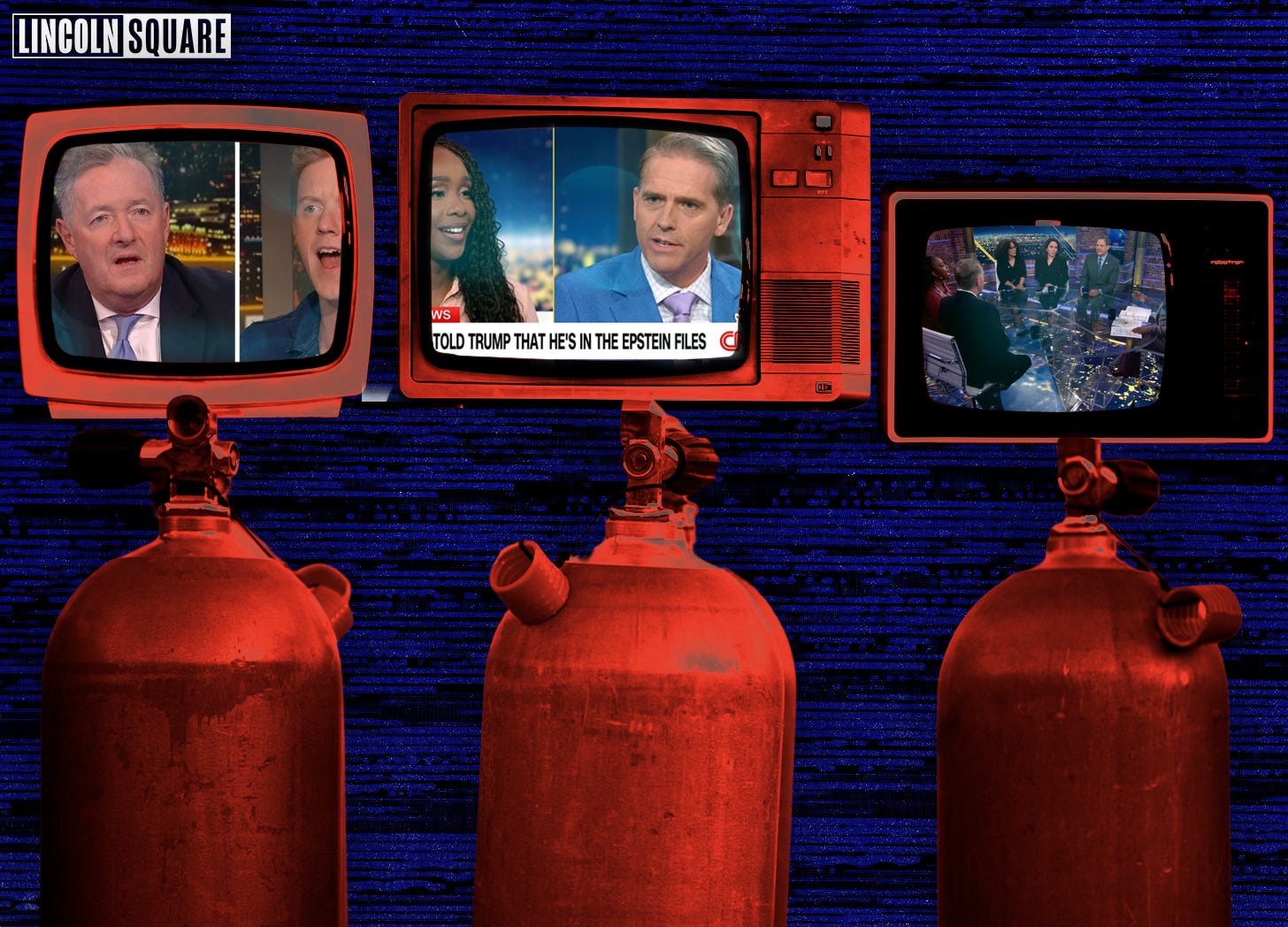

Oxygen journalism is when corporate media breathes life into narratives that should’ve died on contact with reality. It’s the decision to treat attention like it’s harmless, like it’s just “coverage,” when in practice it becomes a ventilator for lies, bad faith, and manufactured controversy. It’s the constant platforming of “debates” over things we already know—like climate change and vaccine efficacy—as if the only reason the public is confused is because they haven’t heard the “other side” enough times. It’s treating issues that should never have been up for negotiation in the first place—like the humanity of Black people (my people)—as if they’re just another spicy panel topic. And it’s keeping professional bad-faith performers on payroll because executives think “loud and wrong” is compelling television.

Which brings me to the Scott Jenningses of the world.

I have made no secret about how much I do not like that entire genre of cable-news personality, and I genuinely do not understand why CNN feels the need to keep them on the payroll if the network truly cares about news and debate. Scott Jennings is clearly not there to debate. He’s there to be loud and wrong on every topic, and CNN keeps treating that like it’s a feature instead of a flaw. The problem is that it serves no real purpose. It contributes to the dumbing down of society. It educates no one. It’s not analysis—it’s noise dressed up as commentary. It’s a human fog machine in a sui

But here’s the thing: I expect this kind of crap from Fox News regulars like Brian Kilmeade, Laura Ingraham, or Greg Gutfeld. I also expect it from the broader conservative pundit-industrial complex—people like Megyn Kelly, Ben Shapiro, and Tucker Carlson—who don’t need a Fox contract to keep the same bad-faith ecosystem humming through podcasts and YouTube. We all know Fox is a clown show, and those personalities aren’t serious people in the first place. My issue is always with the people on the “respectable” side of corporate media who entertain illegitimate debates, because entertaining them is what legitimizes them. Why are we doing this? Why are we pretending that the grown-up version of journalism is putting a liar next to an expert and calling it “balance”?

Now, to be clear, I’m not talking about the elected MAGA officials who go on the Sunday shows and cable news. As much as I can’t stand these people, they do hold actual power, and that means the public has a right to see them questioned. They’re in important positions. We do, unfortunately, have to hear from them. The problem is how often the questioning is framed in a way that gives them room to gaslight instead of forcing them to justify themselves against the actual standard.

Take ICE, for instance. If you watched the clip of Aliya Rahman being dragged from her car by ICE agents in Minneapolis, you saw a moment that should not be treated like a casual “hmm, interesting” debate prompt. The scene was captured and widely circulated, and it triggered the same predictable cable-news reflex: hosts using language like “isn’t this against the law?” as if they’re politely floating a possibility. As if the legal and constitutional standards are a suggestion. As if the question itself is the point.

And that’s the problem. The way the question is couched implies uncertainty about whether the behavior might be legal. That phrasing quietly hands bad-faith guests an opening to narrate over reality. “Well, you don’t know the full context.” “Well, you weren’t there.” “Well, they were obstructing.” “Well, the agents felt threatened.” And suddenly, instead of the guest having to explain why aggressive force was used and whether it was necessary, the audience is watching a fake courtroom drama where the very idea of a standard is treated as up for debate.

This is where oxygen journalism shows itself, because the issue isn’t that journalists should never ask questions. The issue is that journalists shouldn’t ask questions in ways that create wiggle room where none should exist. You don’t start from “maybe illegal?” You start from the rule. You put the standard on the table first, clearly, and then you force the person in power to explain why their conduct meets that standard.

That’s not an abstract point. In Minneapolis, the situation around ICE escalated dramatically after the killing of Renée Good, and it became so charged that a federal judge stepped in with a preliminary injunction limiting what federal officers could do to peaceful demonstrators and observers. The order barred arrests and the use of crowd-control tactics like tear gas against people who were not posing a threat or obstructing. The Trump administration then appealed those limits. That appeal is a real thing that happened, in real time, connected to real protests, connected to a real death, connected to real fear in the community. There was nothing “hypothetical” about any of it. There was no need for a coy little “isn’t this against the law?” framing that invites a bad-faith answer to fill the space. Put the standard on screen, then ask the only question that matters: why was this necessary?

And the Renée Good story matters here because it shows what happens when oxygen journalism runs wild in the same space where people are grieving and demanding accountability. There’s been widespread outrage that the Justice Department said it would not investigate the ICE agent’s fatal shooting of Renée Good, even while federal authorities pursued other investigative avenues aimed at Minnesota officials who criticized enforcement tactics. That decision not to investigate the shooting was not a rumor; it was the kind of official posture that intensifies public distrust and anger because it makes it feel like the state is grading itself on a curve. And while communities were reacting to a killing, the spectacle expanded: mass enforcement operations, political conflict, and a media ecosystem that can’t resist turning everything into a content format. Operation Metro Surge and its impact on Minneapolis has been described in ways that make the climate of fear and disruption impossible to ignore. That’s the environment in which “oxygen journalism” does its worst work—because it turns life-and-death stakes into an argument-of-the-day template.

And here’s the part that drives me up a wall: even when the topic is deadly serious, corporate media will still treat it like a performance of neutrality. The “balance” becomes the priority. The optics become the priority. And when optics become the priority, bad faith becomes a strategy that pays.

That’s why my frustration isn’t just with Fox-style propaganda outlets. It’s with the outlets that know better and still keep doing the same dance. It’s the same problem with CNN booking professional noise merchants. It’s the same problem with the modern debate-panel ecosystem on YouTube, and yes, Piers Morgan is one of the clearest examples of that whole genre.

Because there’s this newer form of journalism—or at least this newer form of political media—that I’m still getting used to. One show I cannot stand is Piers Morgan’s YouTube show, where he has these panels screaming back and forth at each other like the goal is to see who can hit the highest decibel level, not who can provide the clearest explanation of reality. The thing with Morgan’s show is that he often has gifted journalists and communicators on—people who actually do know what they’re talking about. He’s had Krystal Ball. He’s had Emma Vigeland. He’s had David Pakman. He’s had Roland Martin. He’s had Bryan Tyler Cohen. In other words, the show has access to people who can genuinely inform the audience.

But then the setup is almost always the same: pair actual expertise with right-wing lunatics who believe in the dumbest conspiracy theories, and let it devolve into a shouting match. The conversation becomes a “who can yell the loudest” contest. And I do not see how a viewer comes away from those segments better informed. What I do see is MAGA types thrilled that they got to argue with actual experts in their fields. They’re not sitting there thinking, “I hope I learn something.” They’re thinking, “Look at me. I’m on the stage. I’m in the arena.” They’re thinking, “I got invited to the big kid table.”

That’s oxygen.

And it’s not just the panel format. It’s the reward structure. In the clip economy, the goal is not understanding. The goal is engagement. The goal is conflict that can be clipped, posted, reacted to, and fed back into the algorithm. The more absurd the claim, the more it pulls attention. The more attention it pulls, the more the platform rewards it. The more the platform rewards it, the more it gets booked. And then—this is the part that makes it especially poisonous—people defend the whole mess as “fearless debate,” as if debate is automatically a public good even when one side is operating in bad faith.

Oxygen journalism depends on one huge lie: that platforming is neutral.

It isn’t.

The moment you put someone on screen, you aren’t just hearing them out. You’re granting them legitimacy. You’re telling viewers, even subtly, “This person’s worldview belongs in the same room as facts.” And in a culture where so many people already feel untethered from reality—where conspiracy theories spread faster than corrections—that little grant of legitimacy is not harmless. It’s a multiplier.

Which is why the “both sides” defense is always so weak. “We’re just letting viewers decide.” Decide what? Decide whether climate change is real? Decide whether vaccines work? Decide whether Black people deserve basic humanity? Decide whether a woman being dragged from her car by masked federal agents is “maybe” fine if the vibes are right? That’s not journalism. That’s content monetization disguised as civic virtue.

And this is exactly why people like Scott Jennings keep getting booked. Not because they enlighten anyone. They keep getting booked because they maintain the conflict. They keep the argument alive. They throw sand in the gears of clarity. And networks convince themselves that this is “balance,” when it’s really just a business model that can’t resist spectacle.

So yes, that’s what oxygen journalism is.

And I want to be clear about something before anyone turns this into a purity test: I’m not necessarily judging progressives for hopping on these debate-panel shows and debunking lies from conservatives. I understand why they do it. I understand the impulse to show up and correct misinformation in real time, because the truth does matter, and it is infuriating to watch bad faith go unchallenged.

I’m saying I’m still trying to figure out how to navigate this terrain without legitimizing lies—because like I’ve said time and time again, the win for these MAGA types is not out-talking the progressives. The win is that the argument was even had in the first place. The win is that their nonsense got treated like it deserved a seat next to expertise. If you think these MAGA types care about “winning” an argument in any honest sense, I promise you they don’t. They care about sitting at the big kids’ table, and they care that their argument was given oxygen.

There are plenty of legitimate right-left debates that actually deserve airtime because they’re debates about policy, tradeoffs, and governing priorities. I’m for affirmative action; you’re against it. Fine—now we’re debating a policy tool, the intended outcomes, the evidence, the alternatives, and what we think a fair society requires. I’m comfortable with a bigger role for government; you want smaller government. Again—fine. That’s a real ideological debate about the scope of the state. Even debates about the Department of Education can be legitimate: what should it do, what should it stop doing, what should be restructured, what should be devolved to states, how do we measure outcomes, what does accountability look like—those are real questions. But abolishing it entirely shouldn’t be treated like a normal “two sides” conversation as if we’re casually debating whether fire departments are overrated. That’s not a tweak, that’s an arson proposal.

And this is the line corporate media keeps pretending it can’t see: some things are not “debate topics,” they’re bigotry with a microphone. If someone says, “When I see a Black pilot, I wonder if he’s qualified,” that’s not a policy argument. That’s racism. If I “debate” it like it’s a legitimate perspective, I’m not debating a governing framework—I’m debating the merits of prejudice. And bigotry cannot be debated into being respectable. The only thing you accomplish by staging that fight is giving it what it came for: oxygen. The entire point of that kind of statement is to force the room to treat the speaker’s bias like a valid conversation starter. That’s how the lie gets a suit, a chair, and a chyron.

Which is why the idea of Bari Weiss running CBS News is a joke in the first place—because she comes out of the exact culture that confuses “having a take” with having a factual foundation underneath it. She wasn’t hired to turn CBS into a sharper investigative operation; she was hired to recalibrate the optics—more “balance,” more “both sides,” more performances of neutrality that magically end with the most aggressive people in the room getting their worldview treated like a serious alternative to reality. That’s not journalism reform. That’s credibility cosplay with better lighting. CBS’s new ownership installed Weiss as editor in chief of CBS News, and she immediately started talking about overhauling standards and procedures—because nothing says “trust-building” like turning the newsroom into a place where everyone is walking on eggshells, wondering which story is going to get labeled “insufficiently balanced” after it’s already been vetted.

And if you want the cleanest example of how fast that mindset slides into oxygen journalism, look at what happened with 60 Minutes. Weiss shelved a reported segment about Venezuelan migrants being sent to El Salvador’s CECOT prison because it didn’t include an on-camera Trump administration official, even though the team had made repeated attempts and the government refused. The story later aired without that interview anyway—largely unchanged—because the refusal was the point: when the administration declines, that’s still information. But the delay mattered, because the delay teaches a terrible lesson: if you stonewall long enough, you can slow-walk scrutiny. Inside CBS, the reporter described the decision as “corporate censorship,” warning that treating refusal to participate like a reason to spike a story gives officials a functional kill switch over investigative reporting. That’s not “fairness.” That’s handing power a remote control.

And here’s where Bari’s whole brand becomes relevant, because she’s been auditioning for this role for years—publicly performing exhaustion as a substitute for argument. During a panel on Real Time with Bill Maher, she famously declared “I’m done with COVID,” and framed the ongoing public health rules like they were personally harassing her—like the virus was a customer service issue and the regulations were an evil HR department. That moment wasn’t just a throwaway line; it was a worldview: “I’m tired” elevated to a governing principle. And once you’re operating from that mindset, it’s not hard to see how you end up treating journalism the same way—like the job is to manage feelings, not to pin down facts; to perform “balance,” not to hold power to account; to worry about whether the segment has the right optics, not whether the segment tells the truth.

CBS News—and especially 60 Minutes—built its reputation over decades by being an investigative powerhouse, not a “let’s workshop the administration’s preferred framing” factory. But if you put that institution under leadership that treats “both sides” as a sacred ritual even when one side is stonewalling, lying, or laundering cruelty through respectability language, then you’re not just changing management—you’re moving the whole brand straight into the oxygen journalism department.

And before anybody asks me for a neat, emphatic solution here—trust me, I wish I had one. I don’t. What I do know is we’re going to have to demand that news be the one corner of media that tells us what we need to hear, not what it thinks will placate a “side.” Because the second journalism starts treating bad faith like a viewpoint that deserves comfort and equal framing, it isn’t informing the public anymore—it’s supplying oxygen. That’s the trap. That’s the terrain. And that’s why starving bad faith—without surrendering the public square—is one of the hardest media problems of this moment.

Oxygen journalism is what happens when corporate media treats bad faith like a legitimate “side” and then wonders why the public leaves more confused than informed. This piece breaks down how “both sides” framing turns lies into content, why the real MAGA win is getting a seat at the table, and what it does to accountability when news starts placating instead of clarifying.

Thank you Kristoffer! This was an important piece that I hope many read. I've been studying our media industry since Trump came on the scene and I am convinced the media is anything but "liberal" as MAGA love to parrot. We've been conditioned to think FOX is rightwing and CNN is leftwing. That's not the case. I don't know why CNN, NBC, CBS, and ABC report the way they do but it has very little to do with journalism.

Oh, it is. Wrong is wrong no matter how calmly or dressed up it is stated.